The following article ‘What’s Lost as Handwriting Fades’ appeared in the New York Times many years ago, but it remains super relevant to our children today.

Does handwriting even matter?

Not very much, according to many educators.

The Common Core standards call for teaching legible writing, but only in kindergarten and first grade. After that, the emphasis quickly shifts to proficiency on the keyboard.

But neuroscientists warn it’s far too soon to declare handwriting a relic of the past! Evidence suggests that the relationship between handwriting and the rest of a child’s educational development are vital and run deep.

Handwriting Makes Learning Easier

Children not only learn to read more quickly when they first learn to write by hand, but they are also better able to generate ideas and retain information. And, it’s not just what we write that matters — but how.

“As we write, a unique neural circuit is automatically activated,” said Stanislas Dehaene, a psychologist at the Collège de France in Paris. “There is a core recognition of the gesture (or motion) in the written word, a sort of recognition by mental simulation in your brain.

“And it seems that this neural circuit is contributing in unique ways we didn’t realize,” he continued. “Learning is made easier.”

What’s Best? Traced, Freehand or Typed?

A 2012 study led by Dr. Karin James, a psychologist at Indiana University, lent support to that view.

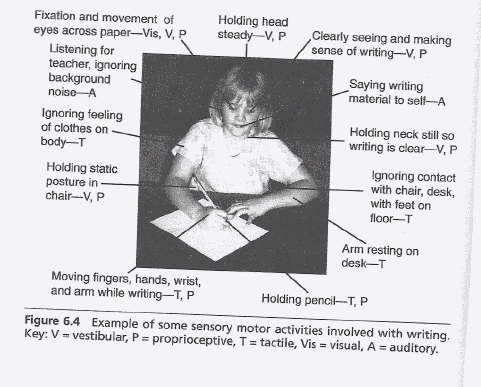

Children who had not yet learned to read and write were presented with a letter or a shape on an index card and asked to reproduce it in one of three ways: trace the image on a page with a dotted outline, draw it on a blank white sheet, or type it on a computer. They were then placed in a brain scanner and shown the image again.

The researchers found that the initial duplication process mattered a great deal.

When children had drawn a letter freehand, they exhibited increased activity in three areas of the brain that are activated in adults when they read and write: the left fusiform gyrus, the inferior frontal gyrus and the posterior parietal cortex.

By contrast, children who typed or traced the letter showed no such effect or brain activation was significantly weaker.

Dr. James attributes the differences to the messiness inherent in free-form handwriting. “Not only must we first plan and execute the action in a way that is not required when we have a traceable outline, but we are also likely to produce a result that is highly variable.”

That variability may itself be a learning tool. “When a kid produces a messy letter,” Dr. James said, “that might help him learn it.”

Our brain must understand that each possible iteration of, say, an “a” is the same, no matter how we see it written. Being able to decipher the messiness of each “a” may be more helpful in establishing that eventual representation than seeing the same result repeatedly.

“This is one of the first demonstrations of the brain being changed because of that practice,” Dr. James said.

Creativity In Learning: Don’t Raise A Child Who’s Afraid Of Mistakes

In another study, Dr. James is comparing children who physically form letters with those who only watch others doing it. Her observations suggest that it’s only the ACTUAL EFFORT that engages the brain’s motor pathways and delivers the learning benefits of handwriting.

The effect goes well beyond letter recognition. In a study that followed children in grades two through five, Virginia Berninger, a psychologist at the University of Washington, demonstrated that printing, cursive writing, and typing on a keyboard are all associated with distinct and separate brain patterns — and each results in a distinct end product.

When the children composed text by hand, they not only consistently produced more words more quickly than they did on a keyboard, but expressed more ideas.

And brain imaging in the oldest children suggested that the connection between writing and idea generation went even further. When these children were asked to come up with ideas for a composition, the ones with better handwriting exhibited greater neural activation in areas associated with working memory — and increased overall activation in the reading and writing networks.

It now appears that there may even be a difference between printing and cursive writing — of particular importance —as the teaching of cursive disappears in curriculum after curriculum.

Cursive: Reasons It Is Still Relevant Today & the Science Behind It

In dysgraphia, a condition where the ability to write is impaired, sometimes after brain injury, the deficit can take on a curious form: In some people, cursive writing remains relatively unimpaired, while in others, printing does.

In alexia, or impaired reading ability, some individuals who are unable to process print can still read cursive, and vice versa — suggesting that the two writing modes activate separate brain networks and engage more cognitive resources than would be the case with a single approach.

Dr. Berninger goes so far as to suggest that cursive writing may train self-control ability in a way that other modes of writing do not, and some researchers argue that it may even be a path to treating dyslexia.

A 2012 review suggests that cursive may be particularly effective for individuals with developmental dysgraphia — motor-control difficulties in forming letters — and that it may aid in preventing the reversal and inversion of letters.

Dyslexia Mystery SOLVED! Meet Sarah Brown Creator Of Dyslexia Games

Cursive or not, the benefits of writing by hand extend beyond childhood. For adults, typing may be a fast and efficient alternative to longhand, but that very efficiency may diminish our ability to process new information.

Two psychologists, Pam Mueller of Princeton and Daniel Oppenheimer of the University of California, LA, have reported that in both laboratory settings and real-world classrooms, students learn better when they take notes by hand than when they type on a keyboard.

Contrary to earlier studies attributing the difference to the distracting effects of computers, the new research suggests that writing by hand allows the student to process a lecture’s contents and reframe it — a process of reflection and manipulation that can lead to better understanding and memory encoding.

Not every expert is persuaded that the long-term benefits of handwriting are as significant as all that. Still, one such skeptic, the Yale psychologist Paul Bloom, says the new research is, at the very least, thought-provoking.

“With handwriting, the very act of putting it down [on paper] forces you to focus on what’s important,” he said. He added, after pausing to consider, “Maybe it helps you think better.”

Maria Konnikova is a contributing writer for The New Yorker online.

A very interesting video on the benefits and history of penmanship and cursive:

“I, Paul, write this greeting with my own hand. Remember my imprisonment. Grace be with you.” ~Col. 4:18

***For the Full Spike Protein Protocol (including NAC) to protect from transmission from the “V” and to help those who took the “V”, go here.

Deep Roots At Home now has a PODCAST! We are covering everything from vaccines, parenting topics, alternative medicine. Head over today and like, share and download a few episodes! https://buff.ly/3KmTZZd

If you want to stay connected, here is one way…

You can also find me on Instagram, MeWe and Telegram.

And please join me for my FREE newsletter. Click here.

©2024 Deep Roots at Home • All Rights Reserved

Related