Hurrah for the mighty heroes of the pollinating world ~ our native bees! From tiny sweat bees to mason and leaf-cutting bees to my favorite, the docile and furry bumblebee, there is an amazing variety of species. Native bees are extremely efficient pollinators, too.

Consider, for example, the 250 female orchard mason bees needed to pollinate an entire acre of apple trees compared to the many thousands of honeybees that it takes to do the same job. Amazing!

Today several of our family went to help bottle the wonderful honey coming out of our hives. It is always a treat to bring that golden near-perfect food home. But it made me think about all the other bees and such that don’t make honey. They do lots of work for us, too.

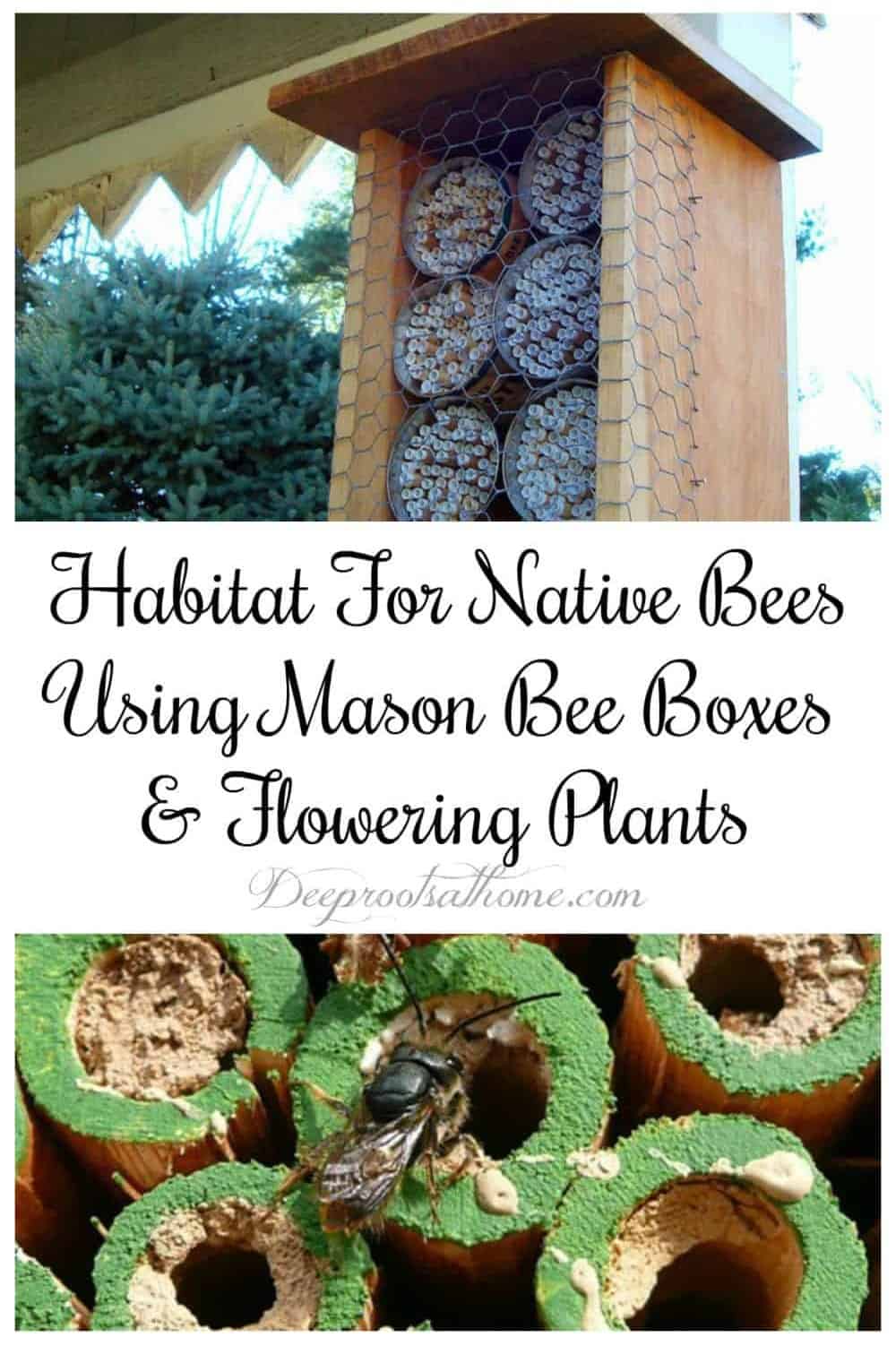

(source-Mason Bees at Morris Arboretum) ~ Note: mason bees don’t sting!

Way back in the early 90s they started referring to non-honey producing bees as pollen bees. Nowadays, we call them native bees! Bumbles are particularly important pollinators for many of our domestic and wild food crops, along with many other flowering plants, because they pollinate flowers in a way that honey bees cannot.

Bumbles perform buzz pollination, in which they vibrate their flight muscles inside flowers, causing pollen to discharge and in the process improving pollination for food plants such as tomato, pepper, blueberry and cranberry ( and many more) as well as many wild flowers. Bumble bees also have fur, which picks up lots of pollen that they carry to other flowers.

I was able to capture this example of buzz pollination as a video. I had never seen this before:

Why Are Pollinators Dying?

You may have read about the devastating European honey bee declines (Colony Collapse Disorder) that threaten global agricultural interests (our food supply)! But our native pollinating bees also show large declines.

Why the sudden declines? There are many possible reasons, but habitat loss and chemicals (pesticides and herbicides) are two reasons.

The good news is that most pollinators are quite gentle when they visit flowers for nectar, and they are not likely to bother you while you hover over them with a camera.

Bee Boxes & Flowering Plants To Attract Native Bees

1.) Having a sustainable wildlife habitat is the first step, of course — one filled with a diversity of pollen- and nectar-producing flowers. Strive to provide native blooms throughout as much of the year as possible. Don’t forget about wildflowers, and consider letting friendly “weeds” such as dandelion have a place in your garden.

Some flowering plants you can install this fall (the best time to plant) are:

- blueberries, currants, goose- and josta-berries, raspberries, and chokecherries/aronia

- witch hazel, pussy willow, and forsythia (three of the earliest to bloom for late winter foragers)

- Russian sage and old-fashioned crysanthemum (bloom late when other flowers are done)

- many of the flowering herbs including basil, all the mints, thyme, lavender, anise hyssop, borage, oregano, marjoram, yarrow, bergamot, feverfew, chamomile, comfrey, and more…

- caryopteris (blue-beard)

- echinacea/coneflowers and black-eyed Susans

2.) Of course, avoid all pesticides, herbicides, and chemical fertilizers!

3.) An easy way to help our native wood nesters is to provide bee boxes in which the females can lay their eggs. Bee boxes in their simplest form are untreated wood blocks with holes drilled into them. Use a variety of hole diameters from 2mm to 10mm to benefit a range of bee species. You don’t need to buy wood — a log or untreated scrap block around the house or yard would work just fine.

Most native bees are solitary bees— rather than building a hive along with other bees. It is the female that stays focused on one job: collecting pollen for her own nest, darting from plant to plant. They then seek out a nest spot to lay their eggs. Depending on the species, this might be a cavity in a tree, a tunnel in the ground, or a rock crevice. About thirty percent of our native bees are wood-nesters, including mason, leaf-cutters, and carpenter bees.

Native bees do not fly far for their source of pollen as do honeybees, so place their nest boxes close to your garden or a food source. Food for them and pollination for you!

(source: Strumelia’s Blog~ a wonderful blog for more information on keeping mason bees)

I have not yet identified this pollinator on the aronia berry flowers this spring. It’s some kind of hover fly, I think.

The tiny, but, beautiful Metallic Green bees captured my attention when I saw them swarming all over a late blooming Russian sage last week.

Their colors are dazzling. There are hundreds and thousands of species of bees. Sample.

If you go outside on a cool day, many of these wonderful specimens will sit still for minutes instead of perpetually darting back and forth. Look for pollinators to photograph with your children; it is the beginning of a neat science study sure to interest many.

The Bumbles are social bees. Colony size is only 50 to 200 compared to thousands of honeybees. This bumble bee nesting box at Garden in the Woods in Framingham, MA, simulates the hole near or at ground level that many bumble bees prefer for nesting.

Here’s a fun fact I discovered while doing a bit of research — many native bees are attracted to the color blue! I’m already thinking about ways to get more blue in my garden.

“As busie as a Bee.” ~John Lyly (Lylie or Lyllie), 1554

“Aerodynamically, the bumble bee shouldn’t be able to fly, but the bumble bee doesn’t know it so it goes on flying anyway.”~ Mary Kay Ash

***For the Full Spike Protein Protocol to protect from transmission from the “V” and to help those who took the “V”, go here.

Deep Roots At Home now has a PODCAST! We are covering everything from vaccines, parenting topics, alternative medicine. Head over today and like, share and download a few episodes! https://buff.ly/3KmTZZd

I am once again being shadow-banned over on FB. If you want to stay connected, here is one way…

Censorship is real. My Pinterest account was just suspended; surprisingly, part of my main board is still available through this link, and it scrolls down a long way so all is not lost! BEWARE of the promotional ads in there! They are not placed by me. Pinterest now sells space in boards for these ads, and Temu is a scam. Do not click on them!

You can also find me on Instagram, MeWe, and Telegram.

And please join me for my FREE newsletter. Click here.

©2025 Deep Roots at Home • All Rights Reserved

Related